For the month of April, Amazon.com is offering the Kindle edition of Ashes & Stones at only $1.99!

For the month of April, Amazon.com is offering the Kindle edition of Ashes & Stones at only $1.99!

An excerpt from Ashes and Stones appears this week in the Lapham’s Quarterly Roundtable. Read it here.

Listen to me talk about Ashes and Stones with Katie and Allie of Herstory on the Rocks. I love that Ashes & Stones actually has a cocktail now! I’m a huge fan of Katie & Allie’s podcast—every week they talk about different women in history, and their take is always surprising and engaging, excited to be in conversation with them.

[Image: black graphic image with a hot pink cocktail glass. A women’s symbol is the garnish. It says the title of the podcast HERstory On The Rocks in hot-pink and white letters]

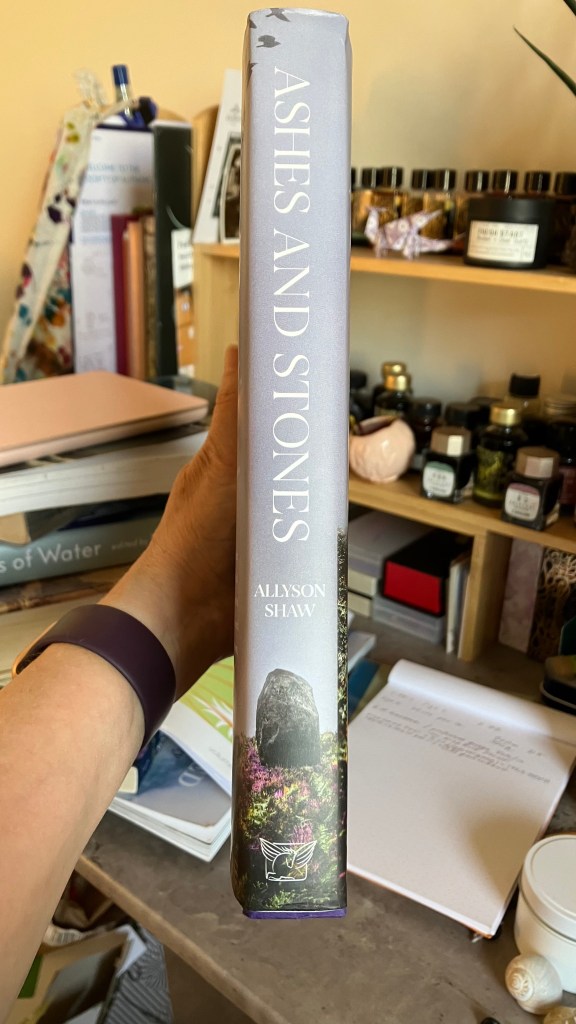

The North American Edition of Ashes and Stones arrived today—published by Pegasus Books in the US on October 3rd. The stone on the cover is the Nicnevin stone in the village of Monzie. Named after the legendary woman burnt as a witch named Kate Nicnevin who also shares a name with Nicnevin, the mythic Scottish witch-goddess and the leader of the wild hunt in lore. According to Sir Walter Scott, she is the “Scottish Hecate.” The most notable fragments of her come to us from 17th century ‘flyting’ poems—word fights where she is mentioned satirically. Yet, in Monzie, magical women, holy wells, cliffs and neolithic menhirs are named after her. I write about this stone and mythic Nicnevin at length in a chapter in Ashes and Stones. It’s so exciting to see the wee stone on the spine of the book!

[IMAGE DESCRIPTION]: Hand holding a hardback book entitled Ashes and Stones. The book has a standing stone in a moor on it and the grey sky is full of ravens. The hand holds the book over a moor of blooming heather and the horizon on the book lines up with the horizon on the photo.]

Pre-oder the North American edition here.

I’ll be speaking at the 40th Anniversary Edinburgh International Book Festival.

I’m on a panel with Mairi Kidd, moderated by Alice Tarbuck.

Wed 16 Aug 13:45 – 14:45 Spark Theatre

Tickets go on sale today, 29th June. You can buy them here.

#EdBookFest23

I’m delighted that Pegasus Books will publish Ashes and Stones in North America. The hardback will be available on 3 October, 2023. Preorders are open now.

a moving reminder for us all to connect with what’s gone before

–The Stylist

Edinburgh friends! Join me at Edinburgh launch for Ashes and Stones at the wonderful Lighthouse Books. I’m overjoyed & honoured to be hosted by Edinburgh’s radical bookshop—an ally to so many communities. 15 February, 7pm. Ticketing information at the Lighthouse Books Website.

For thirty years I have worked in ritual, built altars of words, objects and spaces. I’ve lived by the moon and tides, though I wasn’t always a witch—the word was not there for me to use; it wasn’t something that occurred to me until years later when I embraced the moniker as one of feminist subversion.

It’s October, crone-season, and the 18th is World Menopause Day. Halloween, or Samhain is hot on its heels. The 31st is the witches’ New Year, and as nights grow longer, their attendant twilight will surround us as the veil between the living and the dead thins. It’s a liminal time, as is the menopause, sometimes called “the change.” Winter is coming, and with it, the season of the Cailleach, the Celtic creatrix. This time of year, the Cailleach, the Crone—the archetype of the old woman and the spirit of the land as winter personified, will visit the underworld, carrying with her what we no longer need in that ash-darkened creel on her back.

Now, I am that woman. She is beginning to surface on my own face and hands. My grandmother lived to 96, and I saw her intricately lined face as beyond beautiful. I embrace images of the old woman archetype, marked by her long life, her eyes bright with life force, even while they might be clouded with the blindness of age. The white plait down her back is a trophy of her years. She among all others is privileged with uncountable memories.

While this spiritual notion gives my path of ageing depth and meaning, there is the reality of ageism in this culture, of invisibility and disregard as well as a very real legacy of hatred towards older women, institutionalised in the witch hunts of the 17th century. I have spent the last five years writing about this history, which will now be a book, Ashes & Stones, published by Sceptre/Hodder & Stoughton in January 2023.

Beyond the historical and personal erasure of older women, there is also the daily struggle to access medical care, and the very real symptoms of peri-menopause that for me are nothing less than disabling. I’m 53 and am in what is called peri-menopause, the undefined period of life before menopause, which comes once you have not had a period for a year.

I have fibromyalgia, arthritis, anxiety, depression, and have had suicidal ideation as a survivor of trauma with PTSD. All these things became much worse in my mid 40s, but no medical professional ever mentioned peri-menopause. My friend and dance mentor, Carolena Nericcio, asked me—do you think you are peri-menopausal? I had never heard the word before! No one in my family ever talked about menopause.

Before I had access to HRT, I was severely disabled by pain, depression and anxiety

In my late teens, my boss in the San Fransisco State University Library periodicals department answered some of my questions. It’s fair to say I loved this woman and felt from her a deep protection no one else until that point had given me. She had long, mousey grey hair parted in the middle that she would swing over her shoulder for emphasis. She wore clogs and laughed with all her teeth showing—even the wires of the bridge holding them in place. Her ambling gait made her look like she was always dancing, her straight curtain of hair swinging from side to side down her back. I don’t know how we got talking about the menopause. She was, in many ways, the closest person I had during those troubled years. During the massive earthquake in 1989, we held each other in the doorway of her office, watching the book stacks fall like dominos, people running out from between them, screaming. I cried, and she reassured me it would be ok. She had no idea if that were true, but in that moment it needed saying. She was brave like that, and when we talked about menopause she said, “you just ride it through and it stops.” Maybe a bit like that earthquake–she didn’t need hormone replacement therapy, and my 19 year old self decided at the time that neither would I.

Over the years, I’ve tried to get appointments with my GP to talk about options for dealing with peri-menopause. Every time I brought it up in the past— do you think my pain, depression, hot flashes, chronic yeast infections, UTIs and low mood are peri-menopause? I would get the brush off. Instead, I have been prescribed three different antidepressants. One shut down my brain and body to the point where I was bedridden and, terrifyingly unable to make the decision to go off it. It was essentially a chemical lobotomy. I have refused to take the latest pill prescribed to me, affirming my status as a ‘difficult patient.’ All the NHS offers me now are antidepressants and a rest cure called “pacing” wrapped in a patronising guise of “mindfulness” and “self care”— the blanket and mug of tea as an answer to debilitating chronic illness and peri-menopause.

I began to research, reading good advise on the Reddit Menopause Community—what to ask for, what myths persist in the NHS, and how to insist on your needs. I pursued the HRT idea. I wondered what if there was a therapy I could try safely? Eventually, I was given a phone appointment with a locum (temp) GP who was so uncomfortable with the idea of menopause, he simply couldn’t talk about it. I asked the locum doctor to refer me to the menopause clinic in Aberdeen. He’d never heard of it and didn’t even know there was such a thing. I had to give him the address and information.

While I waited for my appointment with a specialist clinic in the NHS, I had this sinking feeling it would be months, perhaps years, before I saw someone. (I had been on the waiting list for rheumatology for over a year.) I had some savings and I spent it on a private consultation with a menopause specialist. As I waited for an appointment with her (weeks instead of months or years), I, like everyone else of a certain age, watched the Davina truth bomb documentary about menopause. That was in May 2022. I read with dismay the dismissive way the press treated the overwhelming response to the show. They presented menopausal women as trend followers who now sought HRT as some kind of “youth-boosting” fad rather than a legitimate healthcare option.

The private specialist prescribed oestrogen/progesterone patches for me and vaginal oestrogen pessaries. This doctor listened to me, saying the overwhelming majority of women she sees have a similar story to my own, and almost all have been put on at least one antidepressant rather than being prescribed HRT.

Before I had access to HRT, I was severely disabled by pain, depression and anxiety. Every morning it was as if I were hit by a truck, all my confidence and sense of self eroded with the sheer wall of pain and depression engulfing me. Chronic yeast infections and UTIs compounded the misery of it all.

I have been on HRT for four months and my life is utterly changed. Within a day on the patch, I could get up in the morning, make decisions, go for a walk, even. The pain and low mood are still here, but they no longer consume me. I have enough spoons to strategise and plan around them. It was, in short, life changing.

In Scots, an attitude of this sort is called smeddum, and during the witch hunts it was damning. Smeddum means drive, resilience, “vigorous common sense” and resourcefulness—true grit.

Looking back at my writing a book while in this state of suffering seems beyond belief, yet my own ordeal was my link to those accused of witchcraft in the 17th century. Writing about women’s tribulations in a culture that deliberately disbelieves women’s pain gave meaning to the meaningless anguish I faced daily in my own life as well as the women’s lives I researched.

A couple of years ago, I saw the rheumatologist I’d been waiting to see for over a year. When I finally was in front of him for ten minutes he told me that I needed to go back on the pills that laid me low. Before summarily discharging me, he said my suffering was down to ‘my bad attitude.’ In Scots, an attitude of this sort is called smeddum, and during the witch hunts it was damning. Smeddum means drive, resilience, “vigorous common sense”* and resourcefulness—true grit.

talk openly about menopause with everyone. Let it become normal, an everyday thing.

I have smeddum in spades; I write every day, run workshops and continue to live on the earnings from my handmade jewellery business. I survive—financially and spiritually, yet the constant pain and struggle to access care, to be heard, has taken its toll. I am broken in a way I shouldn’t be. Five months from the initial referral, I am still waiting for the NHS menopause clinic appointment.

If you have read this far, I would ask one thing—that you talk openly about menopause with everyone. Let it become normal, an everyday thing. Listen to middle aged women and ask them about their journey through the change. Advocate for them, and take them seriously. Men can be menopausal, too—this is not just about gender, but a complex picture of oestrogen’s role in our minds, hearts and bodies. If you are on this path—here is my hand. Take it. We have prevailed.

I’m so pleased to share the gorgeous cover design for Ashes and Stones by Natalie Chen. The illustrator is Iain MacArthur.

‘It’s summer. I stand where perhaps Ellen stood, in this ground thick with new thistle and long grass. She would have ken this coast in all weathers: in the summer when it was as gentle as a lake and in the winter, with the high winds and stinging salt spray.’

Ashes and Stones is a moving and personal journey, along rugged coasts and through remote villages and modern cities, in search of the traces of those accused of witchcraft in seventeenth-century Scotland. We visit modern memorials, roadside shrines and standing stones, and roam among forests and hedge mazes, folk lore and political fantasies. From fairy hills to forgotten caves, we explore a spellbound landscape.

Out 19 January, 2023. Preorder Now:

Blackwells (offers free shipping to the USA)

Join my Patreon as a Valiant Witness and receive a signed copy of Ashes & Stones. I ship worldwide.